EU RESPONSIBLE DOG BREEDING GUIDELINES

Please note: This document will be a base for developing shorter and user-friendly documents targeted at relevant audiences.

About dogs

The domestic dog (Canis familiaris) has a close and ancient history with humans; together dogs and humans have co-evolved; they can communicate and cooperate with one another and they are able to understand each other’s intentions and they are sensitive to their different emotions. The dog’s ability to form close social bonds with people has meant they have become one of the most popular companion animals in human households.

Dogs are highly social (with other dogs and people), intelligent, playful and agile; they are often more active in the morning and evening, whilst spending large parts of the day resting. Their behaviour and appearance have been shaped by humans through selective breeding.

Dogs have a complex and flexible social life – they can live in multi-sex groups of related and unrelated individuals provided resources allow; they cooperate to defend territories but not to rear young and they form social hierarchies with other dogs.

Free-roaming dogs predominantly scavenge and acquire food from human sources, rather than hunting.

Dogs communicate using visual (body postures and facial expressions) and chemical signals (transmitted through urine, faeces, and ground-scratching); they have a wide range of calls and sounds that provide information on their emotional state. These modes of communication help to moderate their social interactions with other dogs and with people

These guidelines should be read in conjunction with:

- Supplementary Guidance for Responsible Breeders: Early Socialisation and Habituation of Puppies (to follow)

- Guidelines on Commercial Movement of Cats and Dogs (https://ec.europa.eu/food/animals/welfare/eu- platform-animal-welfare/platform_conclusions_en)

- Guidelines for Online Platforms Selling Dogs (https://ec.europa.eu/food/animals/welfare/eu-platform- animal-welfare/platform_conclusions_en)

Acknowledgements:

- Animal and Plant Health Unit, Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Finland

- Animal Health and Welfare Department, National Food Chain Safety Office of Hungary

- Animal Health and Welfare Division, Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine, Ireland

- Animal Welfare Department, Environment Brussels, Belgium

- Animal Welfare Inspector, Transport, Flanders, Belgium

- Animal Welfare Office, Ministry for Agriculture and Food of France

- Animal Welfare Unit, Federal Ministry for Food and Agriculture, Germany

- Animal Welfare Unit, General Direction of Food and Veterinary, Ministry of Agriculture, Portugal

- Animal Welfare Unit, Government of Flanders, Belgium

- Animal Welfare Unit, Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food of Spain

- Animal Welfare Unit, Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality, Netherlands

- Animal Welfare Unit, Public Service of Wallonia, Belgium

- Dipartimento di Medicina Veterinaria, Università degli Studi di Milano, Italy

- Eurogroup for Animals

- Ministry of Health-Izsm, Italy

- Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA)

- State Veterinary and Food Administration of the Slovak Republic

- The Animal Health and Animal Welfare and Veterinary Medicine Units, The Danish Veterinary and Food Administration, Denmark

- The Federation of Veterinarians of Europe

- VIER PFOTEN / FOUR PAWS – European Policy Office European Society of Veterinary Clinical Ethology (ESVCE) National Animal Welfare Inspection Service, The Netherlands Dr Candace Croney- Purdue University

- Uri Baqueiro Espinosa- Queen’s University Belfast

- Tori McEvoy- Queen’s University Belfast

- Nicole Pfaller- Queen’s University Belfast

- Mike Jessop

- Dr Elly Hiby

- Dr Louisa Tasker

- Iwona Mertin

Suggested review of the guidelines:

To keep pace with the evidence-base that underpins best practice for responsible breeding and care of puppies and dogs, the content of these guidelines should be reviewed in 3 years (2023) or earlier if necessary.

CONTENTS

Definitions and terms used in these guidelines 1. Introduction

2. Principles of responsible breeding

3. Selection of parents

3.1 General considerations

3.2 Behavioural traits

3.3 Inherited disorders

3.4 General health requirements

4. Competent human carers

5. Requirements for good animal welfare: Good feeding, good housing, good health and appropriate behaviour

5.1 Good feeding – General

– Adult dogs

– Pregnant and lactating bitches – Puppies

5.2 Good housing – Light

– Noise

– Ventilation

– Temperature

– Accommodation

5.3 Good health – Handling

– Inspection of dogs and puppies – Surgical mutilations

– Veterinary care

– Euthanasia

– Cleaning and hygiene – Isolation facilities

– Emergency planning

5.4 Appropriate behaviour

– Meet dogs’ environmental needs

– Social interaction with other dogs

– Pregnancy and whelping

– Early experience – habituation and socialisation

6. End of breeding life

7. Record keeping

8. Protecting the future welfare of puppies and their new owners 9. Registration, licensing, and enforcement

REFERENCES

ANNEX 1

APPENDIX

RESPONSIBLE DOG BREEDING GUIDELINES

1.- Introduction

Poor breeding practices have profoundly detrimental effects on dog welfare and on the well-being of owners (Croney 2019). The consequences of poor breeding practices may lead to a lifetime of suffering, through poor health and poor suitability as pets, resulting in an untimely death, abandonment or relinquishment. Breeders, legislators, competent authorities, veterinarians, and owners have an ethical responsibility to work together to ensure dogs live a good life.

Dogs and puppies have the same need for a good quality of life regardless of breeding context and all breeders1 are required to act responsibly and with compassion to meet those needs. These guidelines are intended to support the enforcement of responsible breeding and good animal welfare practices by competent authorities. Where national legislation in a country sets higher criteria than those outlined in these guidelines, the national legislation should take precedence.

Research into animal welfare and breed-specific predispositions to disease that inform responsible breeding practices are ongoing; breeders and competent authorities should follow current best practices where these exceed the guidelines. This requires both breeders and competent authorities to regularly update their knowledge of dog welfare.

Animal welfare is a state within the animal that ranges from poor-through-to-good (Broom 1996). For example, poor welfare arises when a dog is sick, injured, or unable to express natural behaviours it is highly motivated to perform; it is associated with negative emotions such as fear, distress, frustration, or boredom. Good welfare results when dogs’ experience positive physical and mental states (Green & Mellor 2011; Mellor 2016), they are thriving – they are physically healthy, and living in a complex environment where they have choice over what they do and when they do things; they feel comfortable and secure; they have access to all necessary resources. Dogs experience a good quality of life when they are thriving.

Breeders have a duty of care, to keep all dogs in a state of good welfare, to ensure puppies have a good start in life – they are functionally fit, healthy and socialised – they fulfil their potential to live a good quality of life in their new homes. Breeders are obliged to find responsible homes for puppies they have bred; ensuring new owners are a good match and understand their lifelong duty of care to their new dog.

2. Principles of responsible breeding

A responsible dog breeder (adapted from RSPCA Australia 2018):

Respects the intrinsic value of dogs

- Demonstrates a genuine concern for the welfare of dogs and their future generations. Avoids breeding from banned breeds and their hybrids, animals that are closely related, or with inherited disorders, or exaggerated features that compromise welfare. Avoids breeding dogs with temperaments that may produce puppies that will be unsuitable pets (e.g. overly reactive, fearful or aggressive towards people or other animals).

Seeks information on the breed at population level and guidance on how to maintain genetic variance of a population

- Demonstrates an understanding of the detrimental effects to the health of future puppies (and population) through inbreeding and avoids the over-use of popular sires and their relatives.

Plans breeding and conscientiously matches puppies with new owners who will be responsible and understand their duty of care towards their dog

- Ensures they can find compatible and suitable homes with responsible owners before breeding.

Optimises dog welfare by providing high standards of housing, husbandry and care that meet the physical and behavioural needs of individual dogs and puppies

- Houses and cares for all dogs and puppies in a way that protects and promotes their welfare, and ensures they experience a good quality of life.

- Ensures that the early experiences of puppies are positive and extensive and shapes their development to be suitable as pets.

- Takes responsibility for the lifetime care and welfare of dogs they no longer breed from. Ensures they are not used for breeding after they are retired, and they are listed as non-breeding, on the relevant Kennel Club register. Provides life-long care or finds them suitable new homes for their retirement.

Demonstrates competency, knowledge of, and a genuine concern for the welfare of the dogs and puppies under their care.

- Through their continued learning, knowledge and actions ensure the highest standards of care are provided for their dogs and puppies.

Must not sell puppies that they have not bred and reared on their premises and must not sell or transfer puppies to third parties

- Recognises the vulnerability of puppies and does not sell or transfer puppies before they are 8 weeks old.

- Does not act as a third party or use a third party for sale or transfer of puppies because it is detrimental to puppy welfare.

- Puppies via a third party are more likely to experience poorer welfare conditions such as early separation from the bitch, additional journeys, and exposure to new environments, which increases the risk of development of behaviour problems (McMillan 2017) and disease.

Is open and transparent

- Keeps accurate records and can provide a complete lifetime history of the dog or puppy under their care.

- Shares the results of clinical examinations and genetic tests of parents.

Provides the new owner with information and support to help them meet the needs of puppies and dogs to live a good life

- Ensures the new owner is compatible with the individual animal and knowledgeable about the welfare needs of their new pet and breed specific requirements.

- Provides up-to-date appropriate information and support to the new owner (even after sale) to help promote the puppies’ and dogs’ quality of life.

Provides a warranty

- Accepts a returned or unwanted animal within a specified time period, for reasons including problems with health, behaviour, compatibility or inability of the owner to provide suitable care.

- Proactively helps to find a more suitable new home for the returned dog.

- Compensates the new owner for any reasonable veterinary costs associated with treatment of a congenital disorder suffered as a result of a breach of the warranty2 (see page 25).

- Protects the statutory rights of the new owner; whether the animal was sold or given away for free.

- When applicable – registers dogs and puppies sold or transferred without a fee as pedigrees ccording to the requirements and codes of practice of governing breed associations and provides new owners with accurate and official breed certificates.

Complies with relevant local, regional, and national legislation, codes of practice or animal welfare standards including any registration and licensing requirements

- Demonstrates compliance with all local, regional and national legislation, and their associated animal welfare standards.

- Exceeds the minimum standards by following best practice, even if that practice is not common in that country.

- Permanently identifies each puppy or dog using a microchip and registering the puppy or dog in the official or recognised database before transfer to the new owner.

- Ensures they (the breeder) are registered as the first owner of the animal.

3. Selection of parents

3.1 General considerations

- Dogs must not be bred which are from breeds (including their hybrids) that are banned by national legislation.

- Dogs used for breeding must be health checked by a veterinarian before breeding; they should be functionally fit, physically healthy (in good body condition and free from obvious signs of infection) and have good (confident and friendly) temperaments – these phenotypes are compatible with a good quality of life.

- Breeders are required to know the specific welfare risks of extreme conformations and inherited disease related to breed or individual (Gough et al 2018). They should avoid breeding dogs for extremes of physical type and minimise the extent of inbreeding (breeding from closely related individuals) which has the potential to be detrimental to the dog’s quality of life.

Where an animal produces puppies with an inherited disease, extreme physical conformations or behavioural characteristics that compromise the puppy’s quality of life, this combination of parents, and their offspring must be excluded from future breeding.

3.2 Behavioural traits

Dogs’ boldness or shyness/fearfulness is heritable; puppies from bold parents behave more confidently around humans, these personality traits have been used to inform selective breeding in working dogs (Saetre et al 2006).

- Breeding dogs should be friendly towards people and other animals, comfortable with being handled and confident living in a home environment, and wider society. Dogs that are fearful or aggressive towards people and other animals should be excluded from breeding.

3.3 Inherited disorders

Avoid inbreeding: Breeding from closely related dogs such as brother and sister, mother and son or father and daughter, grandfather and granddaughter, uncle and niece, predisposes puppies to genetic or birth defects. The degree of inbreeding within a breed should be carefully monitored.

- Inbreeding Coefficient. Selective breeding of individuals should not be undertaken without understanding the genetic similarity between two parents over the greatest number of generations (e.g. at least 10; Dog Breeding Reform Group 2016). Breeders should avoid breeding from individual dogs whose combined coefficient of inbreeding is greater than 6.5% (Dog Breeding Reform Group 2019).

- Popular Sire Effect. The ‘popular sire effect’ reduces genetic diversity of breeds which often leads to deleterious consequences for many future generations (Gough et al 2018). Breeders should avoid overusing stud dogs in the breeding population. As a general rule, dogs should not sire more than 5% of the total puppies, in the specific pedigree population, during a 5-year period (Gleroy 2015).

Use Genetic Screening: Breeders are required to use all available, validated screening tests relevant to the breed3 and in conjunction with veterinary advice, before they choose to breed from a dog (Dog Breeding Reform Group 2017; 2019). Screening tests will identify ‘carrier’ dogs that are unaffected by the disease but carry the mutated gene; breeding between two carrier dogs should be avoided (Dog Breeding Reform Group 2019) to prevent puppies being affected. The results of genetic screening tests should be provided to prospective new owners of puppies.

Use an Estimated Breeding Value: Many inherited disorders and behavioural traits are influenced by multiple genes and environmental factors and cannot be adequately controlled through genetic screening for a single gene test. An Estimated Breeding Value can be used to estimate a dog’s risk of developing complex inherited conditions and the degree to which they may be affected in the future. The estimated breeding value should be considered when deciding the suitability of an individual for breeding. The results of the Estimated Breeding Value should be provided to prospective new owners of puppies.

Avoid breeding for extremes: Dogs may suffer as a result of extreme conformations (British Veterinary Association 2018; Dog Breeding Reform Group 2018). For example, Brachycephalism (being flat-faced; van Hagen 2019) which produces anatomical defects to dogs’ skull affecting the brain, eyes and upper airway, predisposing individuals to life-long neurological and eye-related problems, and difficulties in breathing, sleeping (sleep apnoea), overheating and regurgitation.

- Dogs with extreme conformation4 (or those who have had corrective surgery) must not be bred from (or presented in breeding exhibitions); the corrective surgery should be noted in the relevant health information alongside their microchip registration, and where appropriate health passport.

3.4 General health requirements

- Both bitch and stud dog must receive prophylactic health care under the direction of a veterinarian, including regular vaccinations, thorough clinical examination, and treatment for internal and external parasites. The timing of treatments must be under veterinary direction as some may harm the foetus if given during pregnancy or lactation.

Vaccination

Dogs should be vaccinated by a veterinarian before mating; bitches recently vaccinated before pregnancy will produce antibodies in colostrum (first milk) which will be passed on to puppies during nursing, conferring temporary immunity to specific diseases.

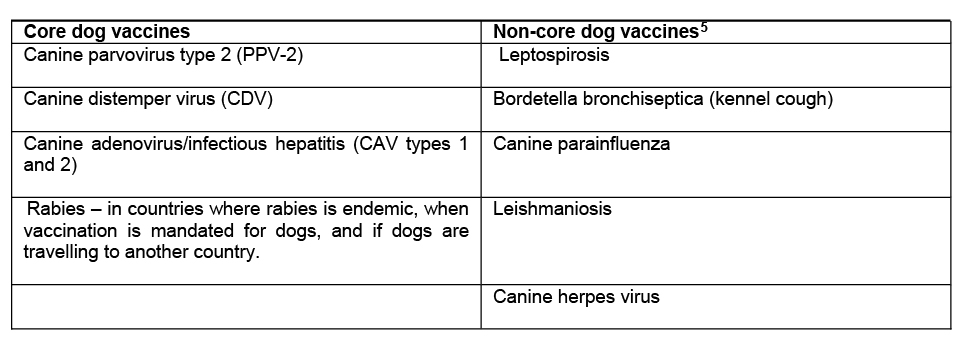

The availability of core and non-core vaccines (Table 1; Day et al 2016) for dogs will vary country-to- country. Veterinarians should follow national guidelines on the vaccination requirements for dogs.

Table 1. Core and non-core vaccines for dogs (Day et al 2016)

For each dog and puppy, breeders are required to keep an up-to-date vaccination certificate signed by the veterinarian. Where appropriate, this should be a national health certificate or European Pet Passport. Homeopathic vaccinations are not an acceptable alternative.

Breeding

- Both parents must be able to mate naturally. Forced matings must not take place.

- Artificial insemination must not be used as a default or to overcome problems due to the inability of the dogs to mate naturally. It may only be considered under exceptional circumstances, and to do so requires strict justification:

-

- Where its use can be demonstrated to lead to an improvement in the welfare of potential offspring by increasing the genetic variability of the breed, thereby reducing the incidence of harmful genetic mutations.

- Both parents must have a previous history of breeding naturally (e.g. mating and giving birth without intervention); it must not be used to overcome physical inabilities of the parents.

- Only manual collection methods can be used to collect semen; electroejaculation methods are not permitted.

- Surgical artificial insemination is not permitted.

- Semen collection and artificial insemination must only be performed by a suitably qualified veterinarian, competent and authorised in the practice of the methods.

- Breeding bitches should be good mothers – able to give birth and rear their puppies naturally (note this information will not be available for first-time mothers). Bitches that have had a caesarean section must not be bred from again unless a veterinarian certifies that it will not compromise the welfare of the bitch to do so. Bitches that have had two litters delivered by caesarean section must not be bred from.

Breeding age

The effects of age interact with other factors such as breed (physical size) and overall health in determining the reproductive fitness of dogs, and the subsequent welfare of their puppies (Fisher & Croney in prep). Breeding should be delayed until dogs are physically mature and should not extend into old-age. Bitches are more likely to experience gestational complications from middle-age; whilst sperm quality declines with age and changes in health status in stud dogs (Fisher & Croney in prep). The ages listed below are given as a guide. It is recommended to let the dogs be examined regularly by a veterinarian, to ensure no objections are found against using the dogs for breeding.

- Bitches and stud dogs must not be used for breeding until they are fully grown (have reached sexual and skeletal maturity) – this age is breed-specific; some larger breeds mature much later. Bitches younger than 18 months of age should not be bred.

- Bitches over the age of 7 years should not be bred unless examined by a veterinarian and when the veterinarian found no objections against further breeding with the bitch. Veterinary advice must be sought before breeding bitches from larger breeds if they are 6 years of age or older. Breeders should avoid breeding bitches for the first time if they are aged 6 years or older. Bitches must not have a litter within 12 months of the previous litter and must not give birth to more than 4 litters in her lifetime.

- Stud dogs over the age of 7 years should be examined by a veterinarian to see whether the veterinarian has no objections against further using the stud dogs for breeding. Veterinary advice must be sought before breeding stud dogs from larger breeds if they are 6 years of age or older.

Mating

- Introductions between the bitch and stud dog must be carefully planned and closely monitored to ensure both are protected from injury or disease. Animals that are incompatible (due to physical size or behaviour) must not be mated. Mating that results in large puppies or large litter sizes may increase the risk of dystocia.

- Mating pairs should be physically separated from other animals. Consideration must be given to the impact a bitch in oestrus may have on other dogs. Facilities must be available to securely separate (including from visual, auditory and where possible olfactory cues) male dogs from bitches in oestrus, to avoid frustration.

- Following mating, breeders are required to carefully check both dogs for signs of injury. Veterinary advice should be sought and followed if necessary.

4 Competent human carers

The welfare of breeding dogs and puppies is dependent upon the environment and care provided by humans.

- Breeders are required to demonstrate evidence of competency (relevant to dog breeding) (to the competent authority) in the following areas:

- Dog welfare – recognise the signs of poor and good welfare, and be able to take appropriate measures to prevent, reduce and mitigate suffering and promote animal welfare.

- Disease control.

- Up-to-date understanding of breed-related disorders (when appropriate). o Recognition and first aid treatment of sick animals.

- Dog behaviour, early development, and socialisation.

- Welfare-centred dog handling and training.

- Environmental enrichment.

- Cleanliness and hygiene.

- Feeding and food preparation.

- There must be enough competent adult human carers available during the day (and where necessary night) to care for dogs and puppies according to the criteria in these guidelines (Section 5). For example, recently proposed amendments to Animal Welfare Legislation in Germany requires breeders to dedicate 4h/day to care for puppies (including time for socialisation)6 to ensure their welfare is protected and they go on to develop into well-adjusted pet dogs. As a guide, breeders should have at least 1 full time, suitably competent individual available during normal working hours, 7 days a week per 10 adult dogs kept, ideally that ratio should be lowered to 1:5 (staff:dog); the effectiveness of care staff-to-animal ratio should be clearly demonstrated in the delivery of animal care outlined in the guidance and should take into account the additional time required for adequate early habituation and socialisation of puppies when litters are present.

- Where breeders are licensed to care for higher numbers of dogs and puppies, they should undertake a recognised dog-appropriate animal care qualification (if available in country). They should also undertake regular continuing professional development training, including the use of online courses and literature to keep up-to-date with good animal care practices. Breeders must be required to demonstrate what training has been undertaken and how often it is completed.

5. Requirements for good animal welfare: Good feeding, good housing, good health, and appropriate behaviour

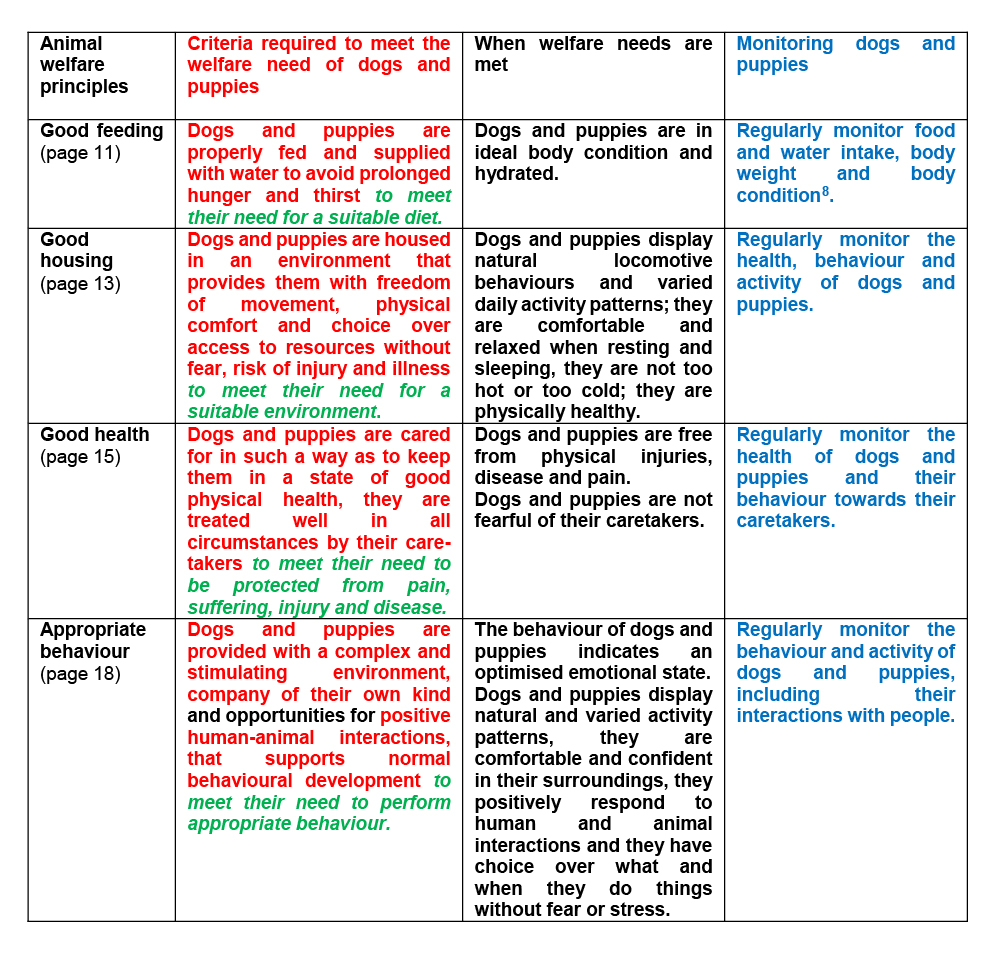

In this section of the guidelines, good animal welfare is considered in terms of four welfare principles (e.g. Welfare Quality): good feeding, good housing, good health, and appropriate behaviour, which reflect the animal’s underlying welfare needs. Each principle has suggested criteria that breeders are required to meet to provide for the welfare needs of dogs and puppies. The welfare of dogs and puppies can be monitored to evaluate whether they are being kept in a state of good welfare.

Table 2. Animal welfare principles, their criteria and suggested welfare indicators

5.1 Good feeding

Breeders are required to:

[General]

- Feed dogs a high-quality complete diet appropriate to their individual needs (e.g. breed, activity levels, age and health or condition).

- Veterinarians or appropriately qualified and experienced animal nutritionists can provide advice on suitable diets for pregnant and lactating bitches, and puppies.

- Give ad-libitum access to water, that is refreshed daily.

- Keep food and water fresh and uncontaminated.

- Store food in a hygienic location and in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions in cool and dry places; and including refrigeration, where required.

- Raw food should be used with caution and only where biosecurity methods are strictly followed, including safe storage and separate preparation areas, with hot and cold running water.

- Store and present food away from the risk of vermin.

- Prepare food in a hygienic location.

- Remove uneaten wet food by the time of next feeding and replace uneaten dried food every 24 hours.

- Introduce new foods gradually, following veterinary or the food manufacturers advice, to allow dogs to adjust.

- Offer food and water in different receptacles (that are non-porous), one food and one water bowl for each dog; site food bowls to avoid food aggression between dogs.

- Provide bitches with food and water that is separate to her puppies.

- Monitor food and water intake each day.

- Seek veterinary advice if adult dogs do not eat for 24 hours or they do not drink, or they drink excessively, or they display pica. Veterinary advice is required sooner if there are specific concerns.

- Ensure dogs that display significant unexplained weight loss or weight gain, or condition are examined by a veterinarian and treated as necessary.

- Regularly monitor body weight and body condition to ensure dogs are receiving the correct nutrition.

[Adult dogs]

- Feed adult dogs at least twice during the day, as appropriate to the needs of the individual unless instructed differently by a veterinarian.

[Pregnant and lactating bitches]

Pregnancy and lactation place increased energetic and nutritional demands on bitches.

- Feed bitches a high-quality diet that is appropriate to stage of pregnancy and lactation, and body condition.

- Ad-libitum feeding with food formulated for puppies, until the puppies are weaned, should provide good nutrition for the bitch. However, care must be taken not to over feed bitches,as being overweight or obese may predispose them to birthing difficulties. Following weaning, the feeding level required will depend upon the bitch’s body condition.

[Puppies]

Maternal milk provides all the nutrients for puppies in the first three weeks of life. Colostrum (the first milk) contains antibodies that confers temporary immunity against some infectious disease to puppies.

- Regularly monitor puppies to ensure they are getting enough milk and feeding well, and they are steadily gaining weight.

- Quietly observe the bitch nursing her puppies to ensure they are feeding.

- Weigh puppies shortly after birth (provided the bitch is content for puppies to be handled), and then daily for the first two weeks of life; puppies can subsequently be weighed weekly until homing or up to 6 months of age. Body weights should be recorded.

- Promptly seek veterinary advice if puppies do not feed properly or do not gain weight; their condition can deteriorate much faster than adult dogs.

- Provide supplementary feeding to puppies until weaning is completed, if the bitch is unhealthy or she is unable to feed them.

- Use a milk formula and bottles specifically designed for puppies.

- Seek veterinary advice and/or follow the manufacturers guidelines about quantity frequency and temperature of the milk feed, and good hygiene practices.

- Sterilise and dry bottles and teats after each use to prevent infection.

Weaning is a gradual process whereby puppies are introduced to a solid diet and their dependence on the milk from the bitch gradually reduces.

- Have a plan for weaning puppies and keep a record of transitional feeding, showing the day-by-day ratio of weaning onto a solid food.

- Gradually introduce and transition puppies to solid food. Weaning must not start before the puppy is capable of ingesting feed on its own, and not before 3 – 4 weeks of age; weaning is generally completed when the puppy reaches 6 – 8 weeks of age. Weaning must not be completed in less than 7 days.

- Provide a good quality puppy food, specifically formulated for weaning, and follow the manufacturer’s instructions on quantity and frequency of feeding. Raw food must not be used for weaning puppies. As a minimum, puppies under 8 weeks of age must be fed at least 5 times daily.

- Ensure puppies are eating the correct share of the feed provided, offering food in separate bowls where possible.

- Offer water from a receptacle that is shallow enough to prevent injury or drowning, but large enough to hold enough water to allow all puppies to drink at the same time should they wish to do so.

Ideally:

- Present food and water in different ways to enrich the lives of dogs and puppies (Section 5.4) (Overall & Dyer 2005; Garvey et al 2016).

- Provide suitable edible chews.

- Present food in different ways using puzzle feeders and feeding devices.

- Part of the daily diet can be used for rewarding behaviour during interaction and training sessions with people

- Provide additional access to fresh drinking water in water fountains.

5.2 Good housing

Breeders are required to provide the following conditions:

Light

Dogs require sufficient periods of daylight and darkness to follow their natural day/night activity patterns

- Keep dogs under natural lighting conditions

o Natural daylight should be provided. Where additional artificial lighting sources are used, they must follow a light period equal to natural day length providing at least 10 – 12 hours of light. Artificial lights must be switched off overnight to provide a period of darkness for a minimum of 8 hours. White artificial lighting, preferably broad or full spectrum (including UV), must provide at least 50 lux at the height of the animals (Ruis & van der Bord 2017).

Noise

- Ensure dogs and puppies are not exposed to excessive or continuous noise (including high-frequency and ultrasound).

- Enclosures must be constructed, designed, and laid out to reduce levels of barking. Dogs should experience predictable positive-human interaction and enrichment to reduce Ventilation frustration in a kennelled environment.

Ventilation

- Ensure dogs and puppies have adequate ventilation to keep the area free of noxious odours and damp and to reduce the risk of infectious bronchitis (‘kennel cough’).

- Bitches with their puppies must be kept draught free.

Temperature

Dogs are tolerant of a wide range of ambient temperatures. Puppies require higher ambient temperatures until they can effectively thermoregulate independently.

[General]

- Ensure dogs and puppies have access to a temperature gradient so they can choose areas that are cooler or warmer depending upon their needs

- Check that dogs and puppies are not too hot or too cold. If dogs or puppies show signs of heat or cold intolerance, steps must be taken to ensure their welfare is protected.

- Regularly check ambient temperatures to ensure the required temperature ranges are maintained:

- Temperatures should be recorded daily, using a maximum/minimum thermometer, [Adult dogs] placed at the height of the dog, and sited as close as possible to the main resting area.

- Ensure indoor accommodation for adult dogs is kept between 10 – 26oC

- An optimal range lies between 15 – 21oC (van der Leij 2009).

- Brachycephalic dogs and those with extreme coat types require careful management as they have markedly different thermal-tolerances (Jordan et al 2016).

[Bitches and puppies]

- Ensure the whelping area is kept between 22 – 28oC

- Newborn puppies require a higher ambient temperature for the first 10 days after birth since they are unable to thermoregulate independently.

- Take care to ensure the area and puppies do not overheat. Additional heat sources must be used safely – they must not pose a burn or fire risk to dogs or puppies or their accommodation. The bitch should be able to move away from the heat source to a cooler area if she chooses to do so.

Accommodation

The type, quality (what the space includes and whether it facilitates performance of natural behaviour) and size of space provided to dogs are important for good dog welfare

Type of accommodation

- Ideally, dogs and their puppies should live in their owner’s home so that they are familiar and comfortable with the domestic home environment and human activities.

- Dogs kept in a home must have free access to more than one room that exceeds the minimum space allowance for dogs (Annex 1), plus access to an outside area for exercise. Dogs must not be confined to an indoor cage or kennel unless for short periods due to ill health under veterinary advice.

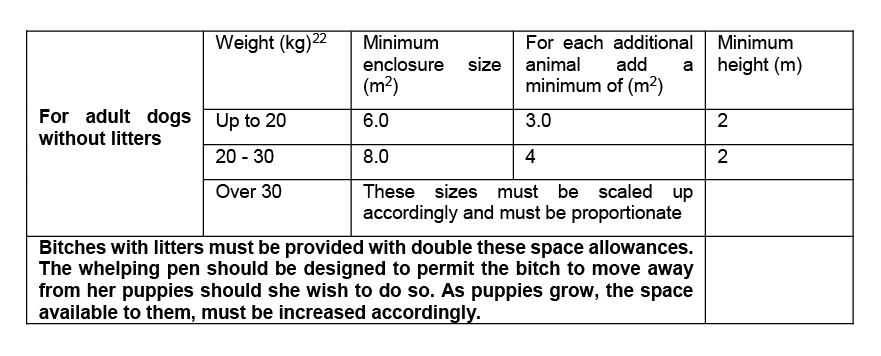

- Dogs kept in a kennel environment must have continual access to an enclosure that includes an indoor sleeping area and an adjoining run or secure outside space that meets and preferably exceeds the minimum space allowance for dogs (Annex 1).

- The enclosure size must increase in relation to the number and size of dogs housed within it (Annex 1). Enclosure design must allow dogs to retreat from events they find alarming at the front of the kennel. Small/shallow enclosures should be avoided as they do not permit this important coping behaviour, enclosures must be no less than 2m in any direction.

- Breeders should provide a detailed floor plan which clearly states the layout and dimensions of animal accommodations.

- Dogs must not be housed in cages that are tiered or stacked on top of one another. Quality of space

- Provide dogs and puppies with a physical environment that is enriched, complex and stimulating, so that they can perform natural behaviour.

- Provide each dog with enough space to walk, run, play, turn around, stand, stand erect on hind legs, wag their tail, lie down fully stretched out without touching another dog or walls.

- Provide dogs with a large enough physical space to allow sleeping and activity areas to be separated and accommodate the inclusion of enrichment; the space should be well designed to avoid competition over resources when dogs are housed in pairs or groups. Dogs must be able to move away from each other should they wish to do so.

- Dogs must have continual access to clean, dry, draught-free sleeping area with appropriate comfortable bedding.

- It is more difficult to prepare kennel-only living dogs and puppies to life in a home environment. Enrichment and socialisation plans should demonstrate how they mitigate this deficit.

Safety

- Ensure all areas, equipment, furnishings and appliances to which dogs and puppies have access are safe; they present minimal risks of injury, illness, and escape

- Ensure all housing and exercise areas are constructed from materials that are robust, safe, durable, impermeable and they are kept in a good state of repair.

- Ensure all internal surfaces are non-toxic to dogs.

- Ensure all surfaces, equipment and furnishings can be disinfected when appropriate.

- Ensure floor surfaces are solid; slatted or wire mesh floors must not be used.

Ideally:

- Provide dogs with large and complex housing spaces that allows them to choose where and when they spend their time

- Space should be well-designed from the dog’s perspective and furnished with additional enrichment (Section 5.4). Dogs should be able to move freely and comfortably in their environment, without competition from other dogs.

5.3 Good health

Dogs and puppies should be treated well in all circumstances by caretakers who promote good human- animal relationships with the dog/puppy’s perspective as the focus of their interactions

Breeders are required to:

Handling

- Handle all dogs and puppies with compassion (Brooke 2019) and appropriately (Yin2011); handling methods must be welfare-centred and must not cause suffering – pain, injury, fear, or distress or pose an increased disease risk:

- Aversive training methods must never be used with dogs and puppies.9 Electric shock collars must not be used. Electric fences must not be used.

- Dogs must be correctly fitted with, and walked using, a suitable flat collar, harness or head collar. Head collars should not be used on puppies, and only used in adult dogs in addition to suitable flat collars or harnesses. Slip leads should not be routinely used, and only when fitted with a ‘stop’ to prevent the lead becoming tight enough to restrict the dog’s airway.

- People who care for dogs must provide positive, consistent and predictable interactions with dogs that are appropriate to the needs of the individual.

- Dogs must not be forced to interact with a person, they must have control over interactions and be able to avoid people should they wish to do so.

- Perform husbandry with the minimum disturbance to dogs and puppies.

Inspection of dogs and puppies

- Observe dogs and puppies regularly throughout the day and as often as necessary to protect their welfare.

- Observe animals for signs of abnormal behaviour, ill health, injury, pain, or suffering. Any abnormalities must be addressed, and advice provided by a veterinarian or certified animal behaviourist must be followed.

- Be familiar with the normal signs of labour/birth10. Veterinary advice must be sought promptly if the bitch seems distressed, and whelping is not progressing normally. Breeders should check that all placentas have been passed.

- Check dogs at the start and end of the working day and frequently during the working day, at least every 4 hours during the day. Do not leave dogs or puppies alone for more than 8 hours overnight. Pregnant bitches that are imminently due to whelp, those in whelp, nursing bitches, and puppies that are not yet weaned must be checked more frequently. Breeders must find a balance between too much interference vs. not being able to identify when the bitch and her puppies are distressed. Video cameras may be used to remotely observe bitches during whelping.

- Check puppies shortly after birth (if the bitch will allow). Keep a record of the bitch’s identification (microchip) number and the time of birth of each puppy; record the sex, weight, colour and identification of each puppy as soon as is practically possible. Bitches may become protective of puppies at whelping, resulting in aggression. Care should be taken when approaching and handling and other animals should also be kept away.

- Closely monitor bitches for signs of eclampsia – the sudden onset of weakness, tremors, collapse or seizures caused by low calcium levels when they are lactating.

- Check dogs and puppies regularly for ecto- and endo- parasites and keep animals clean and comfortable. Dogs will require regular grooming (including brushing, nail clipping, cleaning eyes, ears, nose and teeth)

Surgical mutilations

Surgical mutilations11, including debarking, tail docking and ear cropping, of dogs and puppies are not permitted. It is only allowed if it is deemed necessary and certified in writing by a veterinarian for medical purposes (FECAVA 2004).

Veterinary care

- Ensure dogs and puppies are under the care of a veterinarian12 and follow an agreed health plan.

- Register dogs and puppies with a veterinarian and ensure the contact details of the veterinarian and their out-of-hours provision is known in advance.

- Follow a comprehensive and agreed-upon veterinary health plan, including regular vaccinations, appropriate treatment for internal and external parasites, and clinical examinations performed by a veterinarian. The veterinary health plan should take into account the suitability of the individual for breeding (see pages 8 – 9), and should be reviewed annually, ideally by an independent veterinarian.

[Adult dogs]

-

- Dogs must be examined by a veterinarian at least once per year. Ideally, dogs used for breeding should be examined by a veterinarian more frequently, at least twice per year and before mating.

- Ensure dogs are routinely vaccinated by a veterinarian and keep a certified, up-to-date vaccination record that details the core (and non-core) vaccinations that have been given. Homeopathic vaccinations are not an acceptable alternative.

[Bitches and puppies]

-

- Treat bitches and puppies for internal and external parasites at an appropriate age and interval, and with an appropriate as directed by a veterinarian. Veterinary advice must be carefully followed regarding the type of medication, dosage, route of administration and intervals between treatments as inappropriate treatment can be harmful to puppies. Only licensed products should be used.

- Puppies must be examined by a veterinarian before sale or homing or earlier if the bitch or puppies are showing signs of illness. The health and welfare status of each animal should be certified in writing by a veterinarian before homing, identifying the animal by microchip number.

- Puppies must be vaccinated by a veterinarian.

- Microchip and register puppies with the breeder’s details before they are homed, as a permanent form of identification and to support traceability. Microchipping must be performed by a veterinarian or certified individual, and the transponder must comply with ISO standards 11784 and 11785. Ideally microchipping should occur before primary vaccination to ensure accurate identification of the individual.

- Promptly seek and follow veterinary advice if there is any cause for concern over the animals physical and mental state.

- Treatments must be followed and completed to the specifications given by the veterinarian

- Medication must be authorised for the individual dog or puppy by a veterinarian. o A record of treatment should be kept for each dog or puppy.

- Use medicines responsibly and safely.

- Use medicines in accordance with the instructions of the veterinarian or manufacturer (where they are not prescribed medicines).

- Store medicines safely and securely, and at the correct temperature.

- Safely dispose of medicines, in accordance with the manufacturer or veterinarian.

Euthanasia

- Only euthanise animals on welfare grounds. as deemed necessary by a veterinarian.

- Puppies should not be euthanised only because they do not meet a prescribed breed standard, or because they have a conformational defect that will not affect their welfare, or where the defect can be corrected without compromising welfare as advised by a veterinarian.

- It is unacceptable to euthanise dogs and puppies because they cannot be sold. The owner/breeder should always try to rehome retired breeding dogs and unsold puppies to competent owners.

- Retired breeding dogs should not be euthanised only because they cannot fulfil their function as breeding dogs anymore.

- Euthanasia must be performed humanely and only by a veterinarian.

- Keep euthanasia records for each animal including the reason for euthanasia, date and the name of the veterinarian who performed it.

Cleaning and hygiene

The need to keep dogs and puppies in clean and hygienic environments should be balanced against the need of dogs to feel secure in their environment. Dogs deposit scent through urine, faeces, and anal sac secretions, creating a unique scent profile, that helps them feel safe and secure. Over cleaning (frequent cleaning with disinfectant or strong-smelling products) will remove or mask these important scents from the dogs’ environment.

- Ensure good hygiene standards are maintained in dog and puppy accommodations.

- Inspect daily dog/puppy accommodations, and any furnishings, bedding, or equipmen within it.

- Keep accommodations and any furnishings, bedding, or equipment clean, dry and parasite free. Only clean soiled areas and bedding when necessary in the whelping accommodation – it is important to maintain the bitch’s scent profile and avoid unnecessary disturbance.

- Wash, clean and disinfect bedding and toys when needed and on rotation.

- Perform effective daily spot cleaning; urine and faeces must be removed at least twice daily, and floors dried after cleaning.

- Dogs must be removed from their enclosure whilst it is being ‘wet’ cleaned (e.g. power hosing) or disinfected

- Thoroughly clean and disinfect accommodations, and any equipment, whelping boxes, furnishings, or enrichment items, between different dogs

- Clean food and drink receptacles daily and disinfect weekly

- Keep food preparation areas clean and free from dirt and dust.

- Undertake measures that minimise the risks from rodents, insects and other pests.

- Safely use cleaning and disinfection products.

- Use products that are non-toxic to dogs and the environment.

- Avoid using cleaning products containing Benzalkonium Chloride, high concentrations are toxic to dogs.

- Only give dogs access to cleaned areas once they are fully dry. o Safely store and dispose of cleaning products away from dogs.

- Facilities must be provided for the proper collection, storage, and disposal of waste. Special arrangements must be made for handling hazardous waste according to the legislation in each country.

Isolation facilities

- Ensure appropriate isolation, in self-contained facilities are available for the care of sick, injured or potentially infectious animals (including quarantining new, incoming animals).

- Short-term isolation facilities may be provided offsite by an attending veterinary practice, for very sick animals (the veterinary practice must be able to provide 24-hour veterinary care).

- Site isolation facilities at least 5m away from other dogs to reduce the risk of airborne infection being carried between isolated and healthy dogs.

- Ensure housing and care requirements outlined elsewhere in the guidance are followed for dogs and puppies in isolation to protect their welfare.

- Ensure separate feed and water receptacles, bedding, cleaning utensils and cleaning products are used for animals in isolation.

- Follow good hygiene and biosecurity practices:

- When appropriate, use protective clothing and equipment for use only in the isolation facility.

- Have a separate caretaker for isolated dogs or care for dogs in isolation after all other dogs have been attended to.

- Wash hands and use an appropriate disinfectant after leaving isolation and before handling other dogs.

- Completely clean and disinfect isolation and equipment once it is vacated.

- Plan an appropriate quarantine when introducing new dogs. Veterinary advice should be sought on quarantine plans.

- Ensure dogs imported from abroad undergo appropriate health testing by a veterinarian and the results are known before being introduced to other dogs.

Emergency planning

- Always have a fully stocked and maintained first aid kit suitable for use on dogs andpuppies available and accessible. A veterinarian should be consulted concerning the contents of the first aid kit.

- Have a practical and usable emergency evacuation and contingency plan in place that can protect and accommodate all dogs and puppies, and people who care for them.

5.4 Appropriate behaviour

An enriched environment increases opportunities for dogs and puppies to perform species-typical behaviour (including social interactions with other dogs and with humans), and helps give them control over their surroundings, optimising their physical and mental states (Prescott et al 2004; Heath & Wilson 2014).

Breeders are required to:

Meet dogs’ environmental needs

- Provide an enriched environment for dogs and puppies that meets their needs.

- An enrichment programme should clearly set out how it meets the behavioural needs of dogs and puppies. Enrichment for dogs and puppies should be provided in inside and outside enclosures.

- Enrichment should pose little risk of injury or illness to dogs and puppies. o The effectiveness and safety of enrichment should be regularly evaluated.

Breeders are required to provide dogs and puppies with:

- A safe place – for dogs to rest and retreat where they feel comfortable, secure and protected.

- Each dog must be provided with somewhere comfortable and private to retreat out of sight of neighbouring dogs or people should they wish to do so:

- Provide kennelled dogs with a raised platform for somewhere to hide underneath, and somewhere elevated to climb on to view neighbouring dogs and people outside of their kennel. The dual use of raised platforms gives dogs a sense of predictability and control over human activities in their wider environment. Place comfortable bedding material underneath the platform and ensure platforms are large and sturdy, and stable to comfortably accommodate more than one dog. Platforms may be used by nursing bitches to get respite from their puppies.

- A dog crate can also provide an area for retreat and a raised vantage point. Dogs must not be permanently housed in a dog crate. The crate should be sturdy and large enough for each dog to stand, turn around and lie flat out. It should contain comfortable bedding.

- Each dog must be provided with somewhere comfortable and private to retreat out of sight of neighbouring dogs or people should they wish to do so:

- Exercise

Additional opportunities for daily exercise provide important opportunities for dogs to perform species-typical locomotive behaviour (Hubrecht et al 1992), to explore and to interact with people.

-

- Provide dogs, with the exception of whelping bitches and puppies under 6 weeks of age, with daily opportunities for supervised outdoor exercise away from their enclosure for at least 30 minutes, twice per day. Dogs must be given opportunities for free- running.

- Exercise areas should be furnished with additional enrichment items such as toys, paddling pools, agility equipment and raised platforms to stimulate different types of activity including play. Carers should positively interact with dogs during exercise through play and reward-based training (see below). For some dogs, having close calm, physical contact (e.g. through stroking) with people, is just as important as activity. Dogs should not be forced to be active if they do not wish to do so.

- Outdoor enclosures must have areas that are covered and sheltered to provide protection against extreme weather conditions.

- Dogs which cannot be exercised on veterinary advice must be provided with additional enrichment.

- Positive, consistent, predictable human-dog social interaction (that dogs have control over)

- Dogs who have been socialised with people, readily engage, and interact with them (Hubrecht 2002) and seem to value human company (Wells 2004). Positive human-dog social interaction is rewarding for dogs and is an important form of species appropriate enrichment (Feuerbacher & Wynne 2015).

- Ensure all interactions with dogs are positive, predictable, and do not cause alarm. Interactions with people occur frequently throughout the day as husbandry (e.g. feeding and cleaning) is performed. These events provide important opportunities for gentle and compassionate interaction with dogs and should not be overlooked.

- Provide dogs with additional daily opportunities for interaction with people (outside of normal husbandry tasks). These interactions can be planned around daily exercise.

- Do not force dogs to interact; they should be able to move away from people if they choose to do so.

- Dogs must be trained using positive reinforcement techniques13, to facilitate safe and easy handling. Positive reinforcement training can provide important opportunities for problem solving and give dogs a sense of control.

- All dogs should be trained to walk on a lead, come when called, sit and stay when requested, and to accept physical examination.

- Training should occur throughout the life of the dog; breeders should prepare dogs for retirement and/or homing once their breeding life comes to an end; training plans should reflect preparations to transition dogs into new homes.

- Puppies must receive regular, consistent, and positive handling by humans from a young age (see Section: early experience and socialisation).

- Dogs who have been socialised with people, readily engage, and interact with them (Hubrecht 2002) and seem to value human company (Wells 2004). Positive human-dog social interaction is rewarding for dogs and is an important form of species appropriate enrichment (Feuerbacher & Wynne 2015).

- Feeding

- Providing dogs and puppies with puzzle feeders and offering different food presentations (e.g. scatter feeding dried kibble) actively encourages exploration and problem-solving behaviour. Care must be taken to reduce competition and food aggression between dogs.

- Toys

- Dogs and puppies rapidly habituate to toys; using toys in rotation and in combination with interactive play sessions with people will help to maintain their interest.

- Toys must be safe, thus non-toxic and indestructible; they must be size appropriate to prevent injury (particularly to puppies) and must be checked at least daily, to ensure they are safe.

- Provide dogs and puppies with toys that are specifically designed to encourage chewing; they should be checked regularly to reduce risk of choking.

Social interaction with other dogs

Dogs are social animals; under free-roaming conditions they congregate in social groups, often forming stable relationships with other individuals (MacDonald & Carr 2017). Dogs need and value the company of other dogs and they may suffer when kennelled alone (Taylor & Mills 2007). Compatible dogs show affection towards one another – greeting each other amicably, spending time in close contact, resting together, allogrooming14 and playing with one another. These friendly behaviours help buffer dogs against the negative effects of stressful events, and they are likely to be associated with positive welfare states.

- Dogs that are not behaviourally compatible with other dogs (e.g. fearful or aggressive towards other dogs), must not be used for breeding and should be retired.

- Avoid housing dogs alone in kennels, unless for short periods under veterinary advice or when bitches are whelping and rearing neonatal young puppies.

- Reintroducing dogs back into a group after a period of separation must be done carefully and dogs must be closely observed for signs of aggression, fear, and stress.

- Provide dogs with companionship; kennelled dogs should be housed together in compatible, stable pairs or small groups.

- Dogs should be given opportunities for social interaction with other dogs, this may be facilitated during exercise or walks with their owners.

- Dogs housed together must have enough space and resources to avoid competition. o Ensure companions can comfortably rest or sleep together and apart should they wish to do so.

- The compatibility of dogs must be carefully monitored. Dogs must be carefully observed for aggression during feeding. Dogs must not be muzzled to facilitate group or pair housing or exercising.

Promptly address behavioural problems

- Seek and follow advice from a certified behaviourist veterinarian or an applied animal behaviourist to promptly address any behavioural problems, should they arise.

Pregnancy and whelping

The behaviour of bitches usually changes very little during pregnancy, until a couple of weeks before she is due to whelp, when she may become quieter and start to seek suitable comfortable and quiet areas to whelp.

- Provide bitches with a quiet, safe area, away from other animals to give birth

- Bitches should be introduced to whelping accommodation and whelping bed 7 – 10 days before she is due to whelp15, and must be moved into the whelping bed once signs of whelping are shown. Bitches must be accessible to breeders so that assistance can be provided in the event of an emergency.

- Provide bitches with a whelping bed, with sides high enough to prevent puppies from falling out, and large enough to accommodate her at full stretch as she nurses her puppies; the bed should have sides that prevent newborn puppies from being crushed by the bitch; it should be impermeable and easy to clean. Soft and absorbent bedding must be provided to ensure the bitch and puppies are comfortable.

- Ensure whelping accommodation contains all the environmental resources the bitch needs until the puppies are homed.

- Provide bitches with regular opportunities throughout the day for toileting away from puppies.

- Bitches will need respite from their puppies as they grow and become more mobile; once the puppies are readily climbing out of the whelping bed and if the bitch is content to do so, she can be exercised for periods on her own.

- Keep other animals away from the bitch and her puppies for the first two weeks of life. Litters of puppies from different bitches must not be housed together, unless bitches are already housed in compatible social groups.

Early experience – habituation and socialisation

For puppies to make happy confident pets, they must have positive, frequent, and varied experiences of people, other animals and the domestic home environment early in life. Puppies are particularly sensitive to learning about these types of experiences when they are very young (aged between 3 – 14 weeks). Without the right type of experiences during this sensitive period, puppies may never be fully comfortable living as a pet dog. It is of critical importance that breeders take responsibility for positively shaping the early experience of puppies to prepare them for life in a home environment.

For detailed guidance, read: Supplementary Guidance for Responsible Breeders: Early Socialisation and Habituation of Puppies (LINK).

- ● Puppies must not be permanently separated from the bitch before they are fully weaned and not before they are 8 weeks of age unless it is deemed necessary by a veterinarian.

- Puppies may suffer when they are weaned and removed from the bitch and their littermates too early; they miss out on important experiences that positively shape their ability to cope with new experiences later in life and predisposes them to the development of behavioural disorders.

- Have a socialisation and habituation plan16 in place and dedicate additional time to ensure puppies are adequately exposed to the right experiences early on.

- The plan should be appropriate to the puppy’s age, stage of behavioural development and individual needs.

- Use appropriate infection control measures when introducing puppies to new experiences (see Section 5.3).

- Ensure that the bitch and her puppies can cope with interactions.

- A positive and trusting relationship with the bitch should be established prior to whelping, as this will facilitate socialisation and habituation of young puppies to people and the home.

- Puppies can become overwhelmed when they are exposed to too many things too quickly. The behavioural response of the puppy should guide interactions. Start slowly and gradually allow puppies to interact at their own pace.

- Seek veterinary advice on the welfare considerations and appropriateness of hand- rearing puppies.

- Puppies must not be hand-reared unless it is deemed necessary, for example, if the mother is unwell or unable to nurse.

- Lack of opportunities for social learning from their siblings or their mother places puppies at increased risk of developing behavioural problems later in life (e.g. aggression, fear, anxiety), that demonstrate a reduced ability to cope with unfamiliar surroundings. The early experience of these puppies should be carefully planned to help mitigate for this deficit.

- Puppies must be kept with other puppies in their litter or with puppies of a similar age.

- Regularly and appropriately handle puppies to habituate them to different types of handling and to socialise them with people.

- Handle each puppy gently for short periods of time initially, gradually increasing the duration and type of handling as the puppy ages. Puppies can be handled daily from around 3 days old; handling duration should be short (< 1minute) and frequent (x 2/daily). Handling should include stroking the puppy in preferred areas around the head and along the back to the tip of the tail. These positive interactions should be interspersed with picking the puppy up and examining its eyes, ears, feet and underneath the tail – the types of handling that are critical for providing good animal care in the future. Handling must not be prolonged if the puppy is distressed.

- From 3 weeks of age, puppies should be regularly handled and played with by different people, including adults and children. Veterinary advice should be sought on the appropriate biosecurity measures to be followed by new people entering the facility during this time. As a guide, the interactions should increase in frequency and duration as the puppy ages (e.g. 4 times daily) and last up to 30 minutes. This socialisation is in addition to the types of human interaction that occur around normal husbandry events (e.g. cleaning and feeding); these events represent important learning opportunities for puppies, and they must also be positive.

- Gradually habituate puppies to different textures, sounds and sights they are likely to encounter in households (e.g. appliances, televisions, washing machines and different surfaces on which to walk)

- From 3 weeks of age puppies should be exposed to these different types of experiences for short durations on a daily basis, and in different locations of the home or breeding establishment so that they do not form an attachment to a location (e.g. whelping area or kennel).

- Coupling these experiences with rewards such as food, stroking and play will help puppies form positive associations.

- Provide puppies with regular access to different types of floor and walking surfaces so that they do not develop strong preferences or aversions that will interfere with toileting outside the home.

- Toilet training should start before puppies are 8 weeks of age.

- Puppies over 6 weeks of age must have daily access to outdoor, safe and secureexercise areas for at least 30 minutes per day, except in adverse weather conditions or if veterinary advice suggests otherwise.

- Carefully introduce puppies to other adult dogs, and other animals (e.g. cats) if they share the same household.

- Supervise puppies during interactions with friendly, healthy, vaccinated animals in the same household. Puppies must be introduced to vaccinated, healthy, adult dogs in addition to the bitch.

- Prepare puppies for separation from the bitch and litter mates before homing.

- Puppies over 6 weeks of age should experience short periods of separation from the bitch and their littermates. The duration of separation should be gradually increased with time before homing. Puppies must not be left on their own; this period of separation should be spent positively interacting with a person, through feeding or play, so that they form positive associations with being away from their litter.

- Use a socialisation chart17 to help to guide and keep track of what to do and when, so that puppies are adequately socialised.

6. End of breeding life

Breeders are required to:

- Take life-long responsibility for caring for puppies that do not sell, and bitches and stud dogs that are no longer used for breeding or home them to a responsible owner.

- Breeders should ensure retired bitches and stud dogs cannot be used for breeding and that they are listed as non-breeding on the relevant Kennel Club register. A written contract should be in place with any new owner stating that the dog must not be used for breeding.

The decision to euthanise a dog or puppy must be under the direction of a veterinarian and must only be taken for reasons of ill health or behaviour where the animal’s quality of life is deemed to be poor and cannot be improved by veterinary treatment or behavioural intervention.

7. Record keeping

Breeders are required to:

- Keep accurate and complete records for dogs and puppies. Records should provide a complete account of the dog or puppy’s life history with the breeder, and include: Owner/breeder details

- Unique registration number

- Name and address of where the dogs or puppies are kept.

- Name and address of the owner if this is different to the keeper.

- Animal details

- Name and date of birth.

- Permanent identification number – dogs should be permanently identified by a microchip, both the microchip number and date of implant should be recorded. Dogs and puppies should be registered to the breeder on the national microchip database. o

- Breed (or known breed cross) where appropriate.

- Sex, colour and other distinguishing marks.

- If dogs are registered with a breed association these numbers must also be recorded. o Date of acquisition (when applicable).

- Body weight.

- Date and reason for death (if not euthanised).

Details of veterinary treatment

-

- All veterinary treatment, including regular clinical examinations, vaccination, deworming and flea treatment, any other routine or emergency treatment received, any surgery to correct exaggerated conformations, date and reason for euthanasia and the name of the veterinarian who performed the euthanasia,

Breeding information

-

- Results of all performed tests for inherited disorders and dates of the tests. o Details of animals mated (as above).

- Dates of mating and outcome.

- Date and time of whelping.

- Number of puppies born, sex, colour, distinguishing marks, weight and other significant events, identification.

Rearing information

-

- Date and age of weaning.

- Outline of early rearing conditions and socialisation process. Include details of any periods spent isolated from mother and siblings, and reasons for isolation (e.g. disease, injury, treatment etc.)

Homing/sale details

-

- Dog/puppy identification

- Leaving date and age of dog/puppy.

- Name and contact details of the new owner.

- Breeders/new owners must ensure that the puppies microchip number are registered to their new owners as required by national legislation.

Licensed breeders, who care for several dogs, should keep records of:

-

- All care and husbandry provided.

- All daily checks on the animals.

- Body weight and body condition score of dogs and puppies, on a monthly basis fordogs and weekly for puppies (body weight should be checked against annual veterinary records kept for each dog/puppy).

- The oestrus dates of each bitch.

- Stud dogs – the number of visiting bitches or bitches visited, number of mating’s,number of successful pregnancies.

- Where dogs are under a breeding arrangement the details of such dogs and their whereabouts should be recorded.

- The number of breeding bitches and stud dogs that are retired, their identification andfate after retirement (including date of rehoming and the new owner’s details).

- Details of any isolation cases and the management regime in place.

- Specific information must be recorded for dogs that have come from abroad in-line with animal health legislation (e.g. obligatory blood tests and vaccinations).

All breeders should regularly review their records to inform breeding practices and ensure good welfare of dogs and puppies.

For new owners

The new owner must be given a written copy of all relevant records of the dog or puppy,including:

-

- Treatment records.

- Vaccination certificate or European Pet Passport if this is appropriate.

- Veterinary health check results, including the results of health and genetic screening tests.

- Microchip certificate and instructions for changing ownership details on the register. o Breed association registration certificate (when applicable).

- Five-generation pedigree information (when applicable)

- Details of the breed of each parent where different breeds have been crossed.

Written information must also be provided on dog/puppy care:

-

- The dogs/puppies’ feeding regime.

- Temporary health insurance in countries where this is available. o Advice on habituation, training and socialisation.

- Advice on integration into the new household.

- Advice on animal welfare needs.

- Contact details of the breeder – for advice and warranty.

The puppy contract18 is a good example for breeders to follow to ensure information is provided to new owners.

8. Protecting the future welfare of puppies and their new owners

Breeders have an obligation to protect the future welfare of puppies by finding good homes with responsible owners.

Breeders are required to:

- Make reasonable efforts to ensure the new owner is a good match for their puppies; that the new owner understands and can meet the future welfare needs of the puppy and requirements for lifelong care. Breeders must not home a dog or puppy to anyone under the age of 18 years.

- Make reasonable efforts to ensure that the prospective new owner is not acting on behalf of a third party.

- Microchip and register each puppy or dog in the official or recognised database before homing. The breeder should be registered as the first owner of the puppy.

- Provide prospective new owners with accurate and comprehensive written information about the future welfare needs of the puppy in advance of the new owner’s decision to take the puppy home. When applicable, written information should include guidance about the welfare consequences of the results of parental genetic health screening, conformation issues and breed predispositions to disease/disorders.

- Provide a supply of the puppy’s current diet to the new owner. Two weeks supply would allow gradual change over of food by the new owners if required.

- Prospective new owners are required to visit puppies with their biological mother, and littermates, in the environment where they are kept.

The Puppy Contract and its checklist19 can be used to help guide discussions between breeders and prospective new owners to ensure they understand the welfare needs of puppies.

Warranty

- Breeders should provide new owners with a written warranty, about the puppy:

- The breeder warrants that the puppy:

- is at least 8 weeks of age when homed;

- has received good care and been socialised;

- is in good health unless otherwise stated;

- is microchipped and registered on the official or recognised database.

- Where appropriate, the breeder warrants that the pedigree information/breed registration is correct.

- Assured breeders must demonstrate they meet all the requirements of assured breeder schemes as outlined by the governing breed association.

The breeder warrants to reduce or avoid distress and inconvenience caused to the new owner in the event that the puppy suffers poor welfare as a result of poor breeding practices.

The breeder is required to use information about any health or behavioural issues of puppies/dogs to inform future breeding, rearing and socialisation practices.

- The new owner warrants that:

- they will take the puppy to their veterinarian soon after homing for a clinical examination and advice on preventative health treatments;

- they will register their details as the new owner of the puppy in the official or recognised database;

- they will be able to meet the puppy’s future welfare needs based upon the information

- they have received from the breeder;

- they are not purchasing or obtaining the puppy on behalf of a third-party;

- If they find themselves unable to provide for the welfare needs of the puppy, they will contact the breeder for advice including the option to return the puppy to the breeder.

The Puppy Contract20 is a good example of a warranty agreement between the new owner and the breeder.

9. Registration, licensing, and enforcement

- Breeders are required to be accountable and responsible for their activities.

- Breeders should be subject to legal controls, recommendations appear below.

- Where legislation on dog breeding exists, the following refinements of definition and requirements are suggested:

- All breeders are required to register with the competent authority:

- A breeder is someone who owns or keeps at least 1 female or male breeding dog, whether the puppies they produce are sold or given away.

- The competent authority must make reasonable efforts to verify breeders comply with the requirements outlined in the guidance.

- All registered breeders must provide appropriate written evidence for authorisation by the competent authority to demonstrate that they comply with the requirements outlined in the guidance.

- Once authorised, a unique registration number must be supplied to the breeder.

- The competent authority must keep accurate records of breeder’s registration details (including the date of first registration) and in-line with the requirements stipulated in Commission Delegated Regulation EU 2019/203521.

- The competent authority must set a reasonable maximum time limit for the validity of registration, after which time the breeder must re-apply for registration.

- The breeder is required to notify the competent authority of any subsequent change to the original registration.

- As a minimum, the information required for registration, must include:

- Details of the owner and/or keeper breeding the dogs.

- Details of the dogs.

- An outline of dog and puppy housing, husbandry, care and veterinary provisions.

- Details of breeding activities.

- Details of responsibilities and competencies of human carers.

- Licensed breeders:

o Require a licence from the competent authority if they keep 3 or more breeding bitches. o Breeders require inspection by the competent authority before a licence is granted for the first time.- The competent authority must set a reasonable maximum time limit for the validity of the licence, after which time the breeder must re-apply for a licence.

- The breeder must notify the competent authority of any subsequent changes to the original conditions, for which they are licenced.

- The licence must only be granted based on demonstration of the breeder meeting specified conditions.

- The competent authority is required to keep accurate records of the licensing details for each breeder.

- The breeder is required to keep detailed, accurate records for each animal under their care; records must be available for inspection at any time. Records must be kept for a minimum of three years after the animal is no longer under the care of the breeder.

- The total number (dogs and puppies) and breed of dog kept on the premises must be clearly stated.

- All breeders must include their unique registration codes on all advertisements, and sale or transfer documentation, so that it is clearly visible to prospective new owners.

Enforcement

- Competent authorities are responsible for enforcing legal breeding controls including registration and licensing of dog breeders.

- A key responsibility is to ensure breeders comply with conditions for registration and licensing, risk-based inspections should be undertaken to meet this responsibility

- The competent authority will need to balance the requirement for inspection with available resources. Adopting risk-based control approaches may enable an efficient use of resources, with targeted inspections of vulnerable animals or breeding establishments that pose the greatest risk to dogs and puppies. Complaints from citizens related to welfare concerns for dogs and puppies and infringements of consumer rights should be included in risk-based approaches. Control points should be set and reviewed annually.